- Home

- James Fearnley

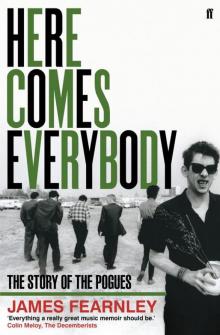

Here Comes Everybody

Here Comes Everybody Read online

Here Comes Everybody

James Fearnley

For Mum and Dad

Contents

List of Illustrations

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Index

Illustrations

Shane and Shanne. (Justin Thomas)

Shane and James. (Peter Anderson)

Shane at Cromer Street. (Iain McKell)

Jem and Marcia at the Empire State Building. (Jem Finer)

The Wag Club. (Deirdre O’Mahony)

Behind the Pindar of Wakefield. (Bleddyn Butcher)

The Irish Centre. (Paul Slattery)

Red Roses for Me beer mat

The Office. (James Fearnley)

The Clarendon Ballroom. (Paul Slattery)

Andrew, Jem and James in a hotel room in Munich.

(Darryl Hunt)

Andrew, Darryl and Debsey at Cibeal Cincise, Kenmare. (Deirdre O’Mahony)

The Boston Arms. (Deirdre O’Mahony)

On the tour bus. (James Fearnley)

‘Dirty Old Town’ video. (Clare Muller)

Reader board. (James Fearnley)

Cait, Frank, Spider and James in Hoboken.

(Photographer unknown)

James and Spider. (Photographer unknown)

Jem, Costello, Cait and Andrew at Tent City.

(James Fearnley)

The Mayor of Derry’s office. (Lorcan Doherty)

Joe Strummer and his guitar. (Steve Pyke/Getty Images)

The Palladium, Los Angeles. (Steve Pyke)

Steve Lillywhite, Kirsty MacColl and Joe Strummer at the

Town and Country Club. (Steve Pyke/Getty Images)

The video for ‘Fiesta’. (Darryl Hunt)

Coram’s Fields Nursery. (Marcia Farquhar)

Bullet train in Japan. (Biddy Mulligan)

Danielle and James. (Biddy Mulligan)

Bob Dylan tour backstage pass

Video shoot for ‘Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah’.

(Bleddyn Butcher)

Joe Strummer at Rockfield. (Darryl Hunt)

Andrew, Jem, P.V. and Darryl at Rockfield.

(James Fearnley)

One

30th August 1991

Shane had gone to his room, stuck phosphorescent planets on the walls and drawn the curtains. Since checking into the Pan Pacific Hotel, on the seafront at Yokohama where we had come to perform at the WOMAD festival taking place in the Seaside Park nearby, none of us had seen hide nor hair of him.

We had arrived in Yokohama from Tokyo the day before, after a brief stopover in London, on our way from a festival in Belgium, the last of a series of European music festivals. Increasingly, our performances had become a matter of determinedly turning a blind eye to Shane’s fitful, fickle behaviour on stage. To keep time, we had resorted to foot-stamping. To find out where we were in a song, we had been forced to commit to prolonged, wretched and discomfiting eye contact.

I was adrift with jet lag. Incapable of staying awake any longer, I’d been waking up just an hour or two after nodding off, to turn the television on and watch CNN, the only channel in English. In the last few days a hundred thousand people had rallied outside the Soviet Union’s parliament building, protesting against the coup that had deposed President Mikhail Gorbachev. The Supreme Soviet had suspended all the activities of the Soviet Communist Party. That the Eastern Bloc was disintegrating seemed apposite to the situation in which we found ourselves.

Yokohama was blazing with sunshine. Against the blue of the sky, the exterior of the hotel was white as sailcloth. It had been a glorious day. I had spent it plying between the hotel and the rumpus of the festival, the hubbub of musicians, techs, drivers, roadies, in the souk of the backstage area, among the caravans and canvas. I adored, in the afternoon sunlight, Suzanne Vega, her hair magenta, accent Californian, pallor Manhattan. I tucked into the crowd with Jem to watch the Rinken Band, a headbanded, muscular bunch from Okinawa. We laughed out loud at their choreography of flexed biceps. They played, to our delight, instruments called shamisens. The thwacks of the plectrum were like firecrackers. It was a joy to spend the day at such a festival, relishing the summer sunlight and the warmth of the evening. I ended the day in jet-lagged, sake-infused awe of Youssou N’Dour, having forgotten for the time being about Shane. Now, as the afternoon turned to evening, I was waiting in my room for the phone call to summon me to a meeting in Jem’s room, to talk about what to do. Though there had been no single catalytic event to join our minds and harden our will regarding Shane – it was just time.

I pictured Shane up in his darkened room somewhere in the hotel as a freakish combination of Mrs Rochester and Miss Havisham, with The Picture of Dorian Gray thrown in. Whenever I thought of him alone in his room, a feeling of impending catastrophe sank my otherwise buoyant spirits. His solitude had started to symbolise the human condition of disassociation, irreducible loneliness, the separation of person from person. What I imagined him doing up in his room, condemned to wakefulness and watchfulness and a horror of sleep – the wall-scrawling, the painting of his face silver, the incessant video-watching – made me fear for us all, for humanity somehow, that all we were heir to was eternally unfulfillable desires and the inevitability of death. I was jet-lagged, was my excuse. Jet lag, along with hangovers, beset me with anxieties that loomed larger than maybe they should. I was filled with worry too at the improbability of putting on a reasonable show tonight, let alone the gigs we had coming up in Osaka and Nagoya before going home.

I had had no desire to go up and see him, no compulsion to drop by. I used to before the Pogues started. His flat was situated at a sort of nexus of my itineraries to and from guitar auditions. I had been drawn to the unmistakable, mardy power he had. Once the Pogues started, I entered into near-constant orbit round him, a decade in which the exigencies of life on the road, the cramped minibuses, the confined dressing rooms, studios, rehearsal rooms, enforced our physical proximity.

Over the past couple of years I had found I didn’t want to be near him. Mostly I didn’t have to be. The Pogues’ continuing success had done away with the tiny vans in which we used to ply the motorways and autobahns and autoroutes at the beginning of our career. By this stage in our lives together, our success had furnished us with relatively commodious tour buses, with a kitchen, bunks, a lounge in the rear. We occupied single rooms in more or less luxury hotels. We played venues, more often than not with ample facilities backstage, with sufficient space for Shane to find a room for himself. By now, I found myself not so aware of Shane’s gravitational pull. I had come to consider myself free of an incumbent responsibility for him, only to be beset by the opposite: a revulsion, a self-protective termination of whatever duty I thought I should have felt towards him, particularly on stage, when the evidence of the torture of his worsening condition over recent years, as he seemed to hurtle to his own self-destruction, had become manifest. I had ended up hating him.

The phone rang

. We were to meet in Jem’s room in half an hour. The occasion for a meeting had become rare enough to be a novelty. It had been several years since we had abandoned our skills at decision-making, suffering as they had from a modicum of success: the hiring of a manager, the signing of a record contract, the engagement of lawyers, an accountant, an agent, the venue for meetings having become the polished desks in lawyers’ premises or the corporate sterility of record company offices or a melamine table with a tray of water, still and sparkling, in one of the conference rooms of the hotel we were staying in. The cumulative effects of our success seemed to have detached us from the ability to husband our creative source.

I was tempted to get excited about the prospect of doing business, taking our careers in hand and sorting things out. Reminded of the circumstances that had prompted the meeting though, I chastised myself. Summoned to the meeting this afternoon in Jem’s room, at a time of day when, given the line-up at the festival, and given the almost pristine beauty of the weather, I would probably have been out at the festival site, whatever excitement I might otherwise have enjoyed sitting around in Jem’s room with my compadres, my brothers-in-arms, my adoptive family, was eclipsed by a feeling of sickness and doom.

They were my compadres. They were my brothers-in-arms. They were my family. Since the chaotic first show at the Pindar of Wakefield in King’s Cross in 1982, we had been together for nine years. It seemed longer than that. We’d gone through a gamut of human experience. We had survived impecuniousness, evictions, sickness and destitution. We had fused our fortunes together in a series of confined spaces: passenger buses, ferryboats, bars, dressing rooms, cabins, restaurants, pubs, hotel rooms. I had lived with these people longer than I had with my own parents, Jem pointed out to me once. I closed the door to my hotel room behind me and climbed the echoing stairwell up to Jem’s floor.

He opened the door. Light from the net curtain at the window lit the corridor. I couldn’t help but try to detect a certain hesitancy or a hint of pessimism in the smile which puckered the corners of Jem’s eyes and revealed the minute serration of his front teeth. In the ten years I had known him, the genuineness of his smile had always been reliable. He stood against the wall to let me in. Even under circumstances such as these, there was a formality about Jem, an understated attention to the matter of putting one at ease. It gave me the feeling that things were going to have a good outcome. I took a seat at the foot of the bed. We awaited the rest of the band. There was a smell of toothpaste in the room.

Whenever there was a knock on the door, Jem got up to greet whoever it was, in the same way he had greeted me. Terry came into the room, carrying, as he did, a pair of glasses in a sturdy case and the book he was reading. He wore jeans and a dramatic black and red short-sleeved shirt, tucked out to hide his stomach. Though he wasn’t a tall man, Terry exuded eminence. He was older than us by a few years. He had curls which were once boyish – a ‘burst mattress’, I used to tease him – but were now greying. He sat on one of the two chairs in the room, his hands folded over his book on his lap, his lips pursed, the expression on his face one of sad seniority, full of the expectation that his years in the music business would be put to use.

Darryl came in and sat in the other chair across from the table, tapping his thighs. His cheeks were laced with capillaries. His bay hair, which he had now begun to dye, fell in brittle unruliness over his forehead. Fatigue had gouged a brown half-moon in the corner of each eye.

Andrew lumbered in. He had grown his hair long. It was beginning to show filaments of grey. He sat heavily on the bed next to me and stared at the carpet. He began to turn his wrist in a hand ivied with veins. His mouth was a lipless line.

Philip came in and wiggled his hand to have space made for him. He perched awkwardly on the corner of the desk-cum-dressing table with his legs crossed, a shoe tucked behind his calf, his frail arms similarly twisted. His hands trembled as he shook a cigarette out of a packet. His mouth was thin, recessive, dwarfed by his fleshy, slightly curving nose. His face was suffused with pink from tiredness.

Spider was the last to knock on the door, apologising for being late. His lips were dry and, with his dark tousled hair, he looked as though he’d just got up. He had a boyish face, even more so this afternoon as he paced back and forth, a hand on his hip, his arm bent awkwardly behind him, the skin on the underside of his forearm wan and subtly grained with the blue of his veins. He clapped his long-fingered hand to the back of his neck, looked down at his shoes and paced between the bed and the wall.

There wasn’t a lot of room. We sat shoulder to shoulder on the ends of the beds or on the dressing table. Terry had the chair and Darryl the armchair by the curtains. By the time we were all gathered the atmosphere was almost funereal.

We talked about our circumstances, what had led us to this meeting, the state of Shane.

In the course of the past two years, our gigs had been decimated by his fits of screaming, his seemingly wilful abandonment of his recollection of the lyrics, his haggard, terror-stricken appeals which we had mistaken for panicked requests for a cue, his maddening and petulant refusals to come out on stage with us.

Jem lamented the fact that Shane no longer accompanied us anywhere, preferring to shut himself in his room, appearing only at show time, more often than not with seconds to spare and hardly in a condition to do much. He lamented the fact that, at one time, Shane would have loved to come to such a festival, the hotel so close, the people interesting, the organisers ready to bend over backwards to help.

‘I miss him!’ Spider complained. ‘I do!’ He laughed at the thought and ruffled his hair with his hand. ‘I miss the cunt!’

‘I’m simply not enjoying myself,’ Andrew announced. We all turned towards him. We knew Andrew well enough. The silence that followed was a precursor to something else. He lifted his eyebrows in weary anticipation of what he knew he was going to say next, resolved to the implications it would carry.

‘He’s spoiling everything.’ He drew in a long breath and cleared his throat. ‘I have a family,’ he continued, ‘what’s left of it.’ Four months before, days after giving birth to their son, Andrew’s wife Deborah had died from an aortic aneurysm.

Terry nodded, and mouthed ‘Andrew’ in sympathy.

‘We all have families,’ Andrew said. ‘Well, most of us.’

He propped himself up, hands on his knees. We waited.

‘I have childcare to pay,’ he went on. ‘I have a mortgage. I earn my living playing music. I can’t do it any more with – him.’ He nodded at the door of Jem’s room to signify Shane, somewhere in the hotel, in his darkened room. Andrew fell silent long enough for us to know he had finished.

‘What do we want to do?’ Jem said then.

‘Let him go,’ Andrew said with a brutality that shocked me.

‘Let him go,’ Spider said.

We went round the room. Philip, Darryl, Terry and Jem were all of the same mind. I didn’t want to let him go. It frightened me to lose what I had become used to, to relinquish pretty much everything I’d wanted since first setting a guitar on my knee and painfully framing chords on it when I was thirteen. I also wanted to punish him. I wanted to drag him round the world with us some more. I wanted to rub his face in his own shit to teach him a lesson.

‘James?’

‘Okay,’ I said.

I hadn’t expected our meeting to arrive so swiftly at such a conclusion, or at any conclusion.

‘Who’ll tell him?’ Jem said. Jem was the perfect candidate. Jem had been the one whose opinion Shane had once sought, and with a meekness which bordered on the reverential. Jem was the one who had badgered him to write, who had set everything up, organised everything. Jem had been the one on whose resolve we had all depended.

In the end though, the task of letting Shane go fell to Darryl. It felt like an act of cowardice, to give the most recent member of the band the job of releasing our singer. But, overriding that, Darryl had the least history with

Shane, had less of an axe to grind, was the least judgemental. Of all of us, Darryl was the nicest.

When the time came, I was shocked that Shane should arrive at the door with such alacrity. Jem got up to let him in. Shane nodded at us all and stood dithering in the short vestibule between the toilet door and the wall.

‘Awright?’ he said. It was a greeting that was as familiar as it was ridiculous in such a context.

There was an endearing vulnerability to him as he turned this way and that, sniffing, taking us all in but unable to meet eyes with any of us with the exception of Jem. Shane followed Jem with a devoted gaze, as he returned to his seat on the end of the bed.

Shane’s hair was filthy. His beard was blasted. His face was the colour of grout. A bib of necklaces, beads and talismans hung from his neck. He was wearing the black short-sleeved shirt which had not been off his back for the past couple of weeks. It was dank with the wearing and had calcimine stains down the front.

‘Can a lady have a seat?’ he said. He dropped into the chair that was found for him and rested a palsied, trembling hand in his lap.

‘Shane,’ Darryl started in. ‘Well, we’ve been having a talk.’

At the end of Darryl’s speech, Shane clopped his tongue to the roof of his mouth and nodded and sat up in the chair and looked at no one.

‘You’ve all been very patient with me,’ he said. He wheezed his laugh of letting air escape where teeth used to be. ‘What took you so long?’

Two

30th June 1980

The studio at Halligan’s rehearsal rooms was narrow. The brown carpeting was sulphurous under the track spotlights in the ceiling and wormed with cigarette burns. A bottle-green set of drums crowded the way in. A guy called Terry sat behind it. He stood up to shake my hand. Beyond, on the brown-carpeted dais at the far end of the room, another guy squatted against the knotted pine dado wiping his nose with the back of his hand. Across from him, a girl leant back against the weight of her white Thunderbird bass. As I worked my way down the room with my guitar, past the edges of the cymbals, the girl appraised me unashamedly – and my new black strides. It seemed she knew how recently I had thrown my flares in the bin. The guy sitting on his heels, in T-shirt, jeans and sandals, forearms on his knees, looked as though he’d had a long afternoon. He pulled on a cigarette and wiped his face. He had watery blue eyes and looked as though he had come off the worse in a fight or two. I could see where cartilage twisted under the skin of his nose and where a kink of scar traipsed from an upturned lip into a nostril. He breathed through his mouth.

Here Comes Everybody

Here Comes Everybody